Extended Abstract:

Simultaneous Caustic Ingestion in Siblings with Divergent Treatment and the Consequences of Health Inequity

William Besley, MD¹; Rebecca A. Carson, DNP, APRN, CPNP-PC/AC²; Annette Roberts, MD³; and John L. Lyles, MD³,⁴

Author affiliations:

Duke University Pediatric Residency¹; Conway School of Nursing, The Catholic University of America, Washington, DC²; Duke University Department of Pediatrics, Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition³; Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC⁴

Background: Accidental ingestion of caustic liquids is uncommon in pediatrics but still poses serious consequences, including pain, stricture, and perforation¹, ². The risk of stricture development increases with the degree and pattern of injury and can lead to chronic pain and malnutrition. Endoscopy is a critical tool to determine the extent of esophageal injury and thereby patient prognosis following caustic ingestions³, ⁴. The Zargar classification ranks esophageal burns from Grade 0 (normal) to Grade IV (perforation) and is the most commonly used tool in grading injury (Table 1)⁴.

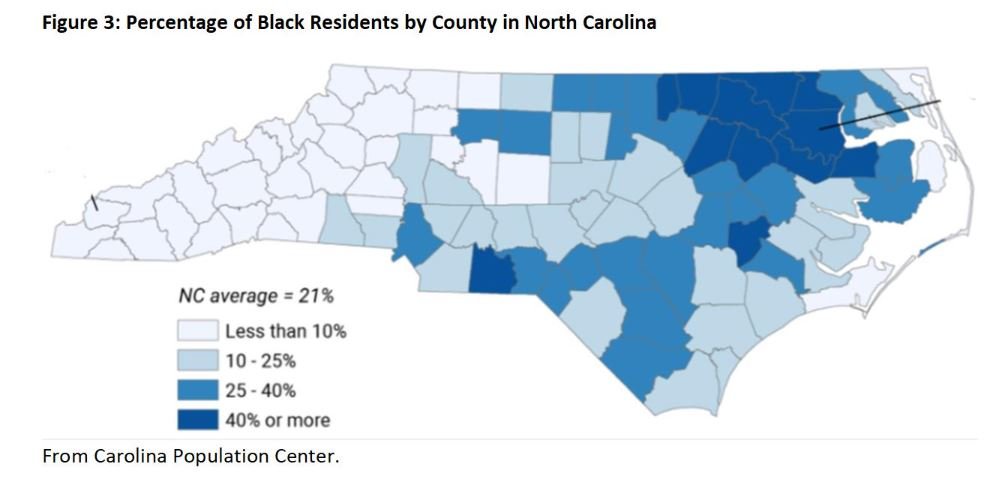

Implicit bias unconsciously impacts provider behavior and clinical outcomes, and healthcare providers demonstrate the same degree of implicit bias as the rest of the population⁸. Children of color commonly experience health inequity because of the interactions of explicit and implicit bias with social determinants of health⁹. North Carolina’s racial minority rates correspond to areas of economic depression (Figures 2 and 3)¹⁰.

Case: Two African American brothers from an impoverished area in North Carolina presented to the Emergency Department (ED) via Emergency Medical Services with rust-colored oral secretions after they each ingested varying amounts of a commercial-grade alkali cleaning detergent that was improperly stored underneath their home kitchen sink. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) was performed within 24 hours of ingestion and demonstrated clinically significant esophageal injury in each child, Zargar IIa for the older brother and Zargar IIb for the younger brother (Figure 4). The children were treated differently based on the severity of esophageal injury, provider experience, level of care, and complications observed. The younger brother received high dose methylprednisolone, high dose proton pump inhibitor (PPI), and sucralfate while the older brother received high dose PPI alone. In the subsequent days, an unfavorable rapport developed between the family and providers that led to bedside disputes, most often citing that the children were admitted to different acuity units and received different treatment regimens.

Prior to discharge, repeat EGD demonstrated esophageal stricture formation in the older brother necessitating esophageal balloon dilation (Figure 5). At discharge, both children were tolerating regular diets with minimal pain. Unfortunately, they were lost to follow-up and ultimately presented to an outside hospital ED months later due to symptom recurrence. The younger child with the more severe injury initially had by then developed 2 discrete strictures with approximately 50% stenosis, though he was still able to tolerate food by mouth. The older child with less severe injury initially, however, met indications for gastrostomy tube placement after he was found to have a stricture with >95% stenosis months later. Unfortunately, at the time of this abstract submission, both patients remain lost to follow up with our group.

However, initial management of esophageal injury due to caustic ingestion is controversial as multiple studies document differing outcomes, especially with respect to the use of steroids⁵, ⁶. Regardless, patient follow-up, including repeat endoscopic evaluation and intervention¹, is necessary for patients with severe injuries. Adequate follow-up can be difficult and is impacted by many factors, including social determinants of health. If left unaddressed, these can lead to health disparities, which disproportionately affect people from communities that are often marginalized. Structural racism is a historical underpinning whereby people from marginalized groups experience strategic discrimination, which leads to inequities in social determinants of health (Figure 1)⁷, ⁸.

Conclusion: Classifying esophageal injury based on endoscopic findings is a difficult task given the subjective categorization of objective findings. Initial classification determines management pathway, but controversy regarding the best evidence-based treatment can complicate initial decision making. For instance, the minor differences between Zargar IIa and IIb result in markedly different treatment recommendations. The gastroenterologist should consider when algorithmic care can be detrimental, and the importance of the holistic patient when determining longitudinal care. Managing children with newly diagnosed chronic health needs is difficult for caregivers, both emotionally and functionally in the context of their existing home life. This can be even more difficult for families that have health disparities or who have been subject to systemic racism. Healthcare providers should examine their own implicit biases and screen for disparities that could lead to health inequities. The side-by-side comparison between two siblings with similar caustic ingestions (time, substance, genetics) initially offered the unique opportunity to compare the clinical outcomes of the divergent treatment recommendations; however, due to the loss in follow up and subsequent development of complications, it has become a more opportune moment to discuss health equity in pediatric gastroenterology. Simple best practices employed by individual health care providers should be the standard of care to combat explicit and implicit bias (Table 2)¹¹.

References:

1. Hoffman RS, Burns MM, Gosselin S. Ingestion of Caustic Substances. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 30;382(18):1739-1748. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1810769. PMID: 32348645.

2. Honar N, Haghighat M, Mahmoodi S, Javaherizadeh H, Kalvandi G, Salimi M. Caustic ingestion in children in south of Iran. Retrospective study from Shiraz - Iran. Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2017 Jan-Mar;37(1):22-25. English. PMID: 28489832.

3. De Lusong MAA, Timbol ABG, Tuazon DJS. Management of esophageal caustic injury. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2017 May 6;8(2):90-98. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v8.i2.90. PMID: 28533917; PMCID: PMC5421115.

4. Zargar SA, Kochhar R, Mehta S, Mehta SK. The role of fiberoptic endoscopy in the management of corrosive ingestion and modified endoscopic classification of burns. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991 Mar-Apr;37(2):165-9. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(91)70678-0. PMID: 2032601.

5. Usta M, Erkan T, Cokugras FC, Urganci N, Onal Z, Gulcan M, Kutlu T. High doses of methylprednisolone in the management of caustic esophageal burns. Pediatrics. 2014 Jun;133(6):E1518-24. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3331. PMID: 24864182.

6. Bonavina L, Chirica M, Skrobic O, Kluger Y, Andreollo NA, Contini S, Simic A, Ansaloni L, Catena F, Fraga GP, Locatelli C, Chiara O, Kashuk J, Coccolini F, Macchitella Y, Mutignani M, Cutrone C, Poli MD, Valetti T, Asti E, Kelly M, Pesko P. Foregut caustic injuries: results of the world society of emergency surgery consensus conference. World J Emerg Surg. 2015 Sep 26;10:44. doi: 10.1186/s13017-015-0039-0. PMID: 26413146; PMCID: PMC4583744.

7. Maria Trent, Danielle G. Dooley, Jacqueline Dougé, SECTION ON ADOLESCENT HEALTH, COUNCIL ON COMMUNITY PEDIATRICS, COMMITTEE ON ADOLESCENCE, Robert M. Cavanaugh, Amy E. Lacroix, Jonathon Fanburg, Maria H. Rahmandar, Laurie L. Hornberger, Marcie B. Schneider, Sophia Yen, Lance Alix Chilton, Andrea E. Green, Kimberley Jo Dilley, Juan Raul Gutierrez, James H. Duffee, Virginia A. Keane, Scott Daniel Krugman, Carla Dawn McKelvey, Julie Michelle Linton, Jacqueline Lee Nelson, Gerri Mattson, Cora C. Breuner, Elizabeth M. Alderman, Laura K. Grubb, Janet Lee, Makia E. Powers, Maria H. Rahmandar, Krishna K. Upadhya, Stephenie B. Wallace; The Impact of Racism on Child and Adolescent Health. Pediatrics August 2019; 144 (2): e20191765. 10.1542/peds.2019-1765

8. Morgan, J. D., De Marco. A. C., LaForett, D. R., Oh, S., Ayankoya, B., Morgan. W., Franco, X., & FPG’s Race, Culture, and Ethnicity Committee. (2018, May). What Racism Looks Like: An Infographic. Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Available at: http://fpg.unc.edu/sites/fpg.unc.edu/files/resources/other-resources/What%20Racism%20Looks%20Like.pdf

9. FitzGerald, C., & Hurst, S. (2017). Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC medical ethics, 18(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-017-0179-8

10. North Carolina Health Equity Report 2018. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities in North Carolina.

11. Cheng TL, Emmanuel MA, Levy DJ, Jenkins RR. Child Health Disparities: What Can a Clinician Do? Pediatrics. 2015 Nov;136(5):961-8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-4126. Epub 2015 Oct 12. PMID: 26459644; PMCID: PMC4621792.